The Passengers

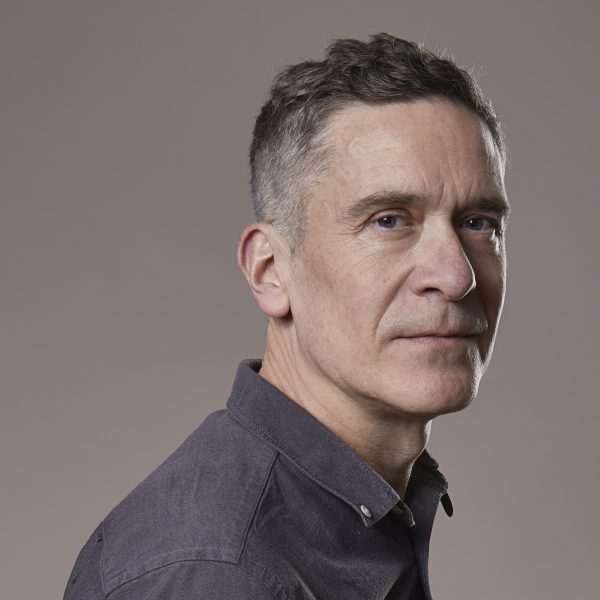

Will Ashon

Will Ashon’s book The Passengers offers a glimpse into the hearts and minds of people across the British Isles (including Dumfries and Galloway!). From October 2018 to March 2021 he spoke to more than 100 people by phone, in person or online. They told him their hopes, dreams and secrets. The book has been highly praised by the The Guardian and others. We asked Will five questions ahead of his appearance at Wigtown Book Festival.

Did what people told you affect your image of British society today?

I think what people told me affected my image of people, rather than of British society, which seems a more nebulous concept than ever. Being forced to engage with other humans always reminds me that most people are alright - thoughtful, self-aware and generous towards others (although it’s possible that this is self-selecting as these types of people are more likely to consent to being interviewed).

We’ve been encouraged for the last 40 years to think of ourselves as atomised individuals rather than as part of a complex organism called society. This tends to lead to mistrust of others and makes it easy to hype conflicts between apparently opposed groups (culture wars, for want of a better term). This means that we miss the huge commonalities that we share and fight like rats in a sack whilst the people who benefit from this lack of unity cream huge profits off the top of us all. I read recently that in workplaces where everyone has a say on wages, the normal distribution agreed upon is that the top earners get 5 times as much as the bottom earners. How far are we from that?! And this is exactly why the people at the top end of our distribution of wealth and income don’t want us all talking to each other as equals.

How did you come to speak to people in Galloway?

I developed a lot of methods for finding people to interview for the book, the idea being to allow some element of chance into the process - some examples are going hitchhiking and interviewing everyone who gave me a lift, or writing letters to random addresses. Another idea I had was to get a map of Britain and then draw lines on it, before finding interviewees along these lines. The first one I drew ran from where I now live through where I grew up. That line eventually ended up passing just south of St Kilda, but also went right through Dumfries and Galloway.

I came to Wigtown in 2017 to talk about my book Strange Labyrinth, so I emailed Adrian a picture of the line and asked if he knew anyone who lived along it. Adrian instead suggested that I join the festival again, which was online that year. So I came along for the Bookshop Band’s morning “chat show” and put my appeal out via this route. I got what I needed….!

Do you think the responses you had would have been very different in the past - say the 80s?

I think what the book is about, at root, is what it feels like to be alive at a particular time and place - here and now. Some things about what it feels like to be alive are fairly universal, others are extremely specific. So I think I would’ve got completely different answers in the ‘80s but something in them would still mean something to us now. On one scale we are all very different, but on another we are all pretty much the same. If you read Henry Mayhew’s monologues in “London Labour and the London Poor” the lives evoked seem very alien to our own but also very similar, essentially human.

Do people find it easier to confide in a stranger - even one writing a book about what they say?

One of the things I decided early on was that I would always choose to believe my interviewees, unconditionally and at all times. Also, I suppose I chose to believe in their ‘goodness’. I wonder whether treating people in this way affected how they answered and what they said? i.e. whether it’s easier to confide in someone who you don’t feel judged by (or who you feel judged well by). Lots of people said it was like a free therapy session, which is terrifying, as I am not a therapist! But maybe that’s what they meant - that it felt safe in some way, less because I was a “stranger” than because they felt that I was “on their side.” Although many of the conversations were actually quite short, it was also very intimate. That was interesting and uncomfortable and fascinating all at once.

Is there anything distinctively British (Scottish, Welsh, English, Northern Irish) in what people said - or would you have got much the same in France, the USA or Japan?

See my answers above! I’m not sure the nation-state is really such a great way for dividing people into groups and divining ‘character’ - usually this is used as a consent-building project for some sort of exclusion, appropriation, war or imperial venture. I would love to see a world without borders. It is true, however, that each of us has a character formed from very specific things; our relationship with the adults who raised us, geography, education. But also very general things (our relationship with the adults who raised us, geography, education etc!). So the book would have been very different if I had interviewed any other 179 people, whether they were all from France or Japan, or indeed all from Dumfries and Galloway. But I think, at its root, it would have been pretty much the same. When you think about it, it’s so remarkable to be alive and conscious of being alive, even if only for a blink of an eye in terms of the universe we exist in. And I think it’s that spark of life which animates the book through these specific testimonies.